Zionist Architecture of the First Two Decades of the 20th Century: From Orientalism to Occidentalism

DOI: https://doi.org/10.34680/urbis-2021-1-172-188

Vladimir Ruzhansky

Russian-Armenian University, Armenia

[email protected]

ORCID: 0000-0003-3590-0124

Abstract

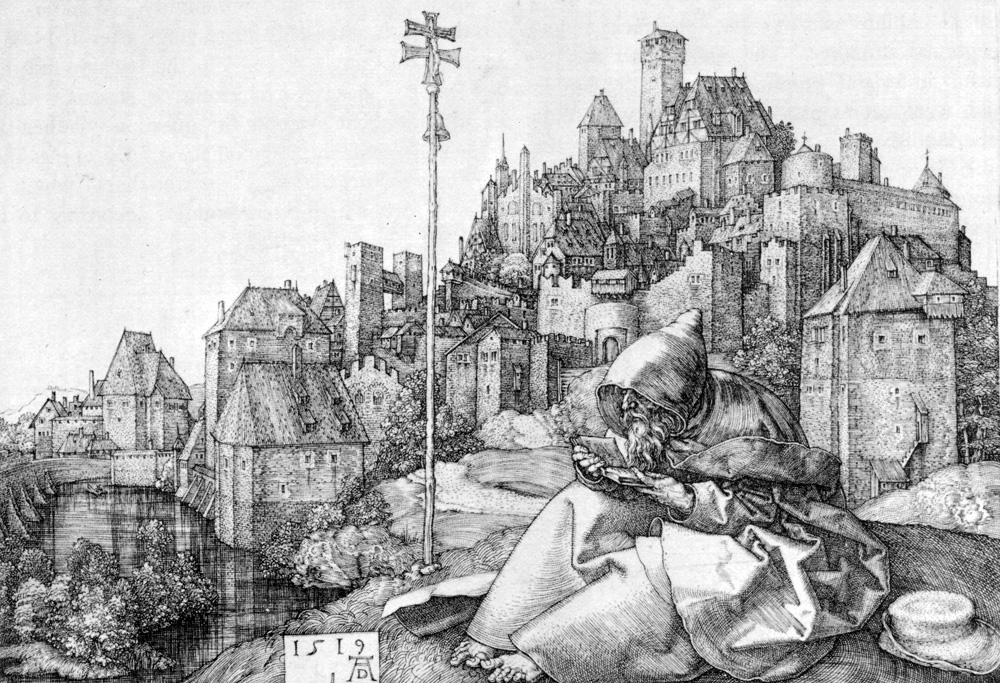

This article is devoted to the history of Zionist Orientalism in Tel Aviv architecture. For a long time, this topic was a kind of taboo in Zionist historiography due to political reasons caused by the Arab-Israeli conflict. For this reason, Zionist Orientalism is still one of the least studied topics in the history of modern Israel. Meanwhile, this trend, albeit for a short period of time, was dominant in Zionism at the beginning of the 20th century. The most famous representative of this trend was the philosopher and theologian Martin Buber. In architecture, Zionist Orientalism was embodied in a special style known as “Eretz Israel”. This style combined the Arab tradition, the Moorish or pseudo-Eastern direction in European architecture of the 19th century, and the ideas of Zionist architects about how the First Temple should have looked. It is important to emphasize that this architectural style was a kind of Zionist manifesto, proclaiming a break with anti-Semitic Europe and at the same time the readiness of Jews to integrate into the Arab East. However, the permanent Arab-Israeli conflict, which originated with the Jewish pogroms in Palestine in 1920, completely changed the outlook and sentiments of the Zionist pioneers. In addition, the romantics from the First and Second Aliyahs in the third decade of the 20th century were replaced by pragmatists – representatives of the middle class from Eastern Europe, for whom the utilitarian component of the city under construction was much more important than the ideological one. As a result, “Eretz Israel” gave way to a new style – the utilitarian,

European “Bauhaus”. The article details the dramatic history of architectural changes that took place in the young city over the course of one decade – from 1909, when Tel Aviv was founded, to 1920, when the conflict between Jews and Arabs turned into a stage of bloody confrontation. The article also analyzes the factors that determined the fate of not only the architectural style “Eretz Israel”, but also the further development of the first Hebrew city in Eretz Israel. To solve these problems, research methods such as comparative historical and historical psychological analysis are used. The central place in this article belongs to the history of the two main streets from which Tel Aviv began, namely, Rothschild Boulevard and Herzliya Gymnasium. The first set is the vector for the development of the city. As for the Herzliya gymnasium, which symbolized Zionist Orientalism, its history ended in the early sixties of the last century, when the building was completely destroyed. The destruction of the gymnasium building and the construction of a high-rise building in its place was also symbolic – Israel finally abandoned Orientalism and the Zionist romance inextricably linked with it and took a decisive course toward the West. The architecture of today‘s Tel Aviv is the result of the development and struggle of these two trends.

Keywords: “Eretz Israel”, Tel Aviv, Zionism, Orientalism, architecture, semiotics.

REFERENCES

Aleksandrowicz 2013 – Aleksandrowicz O. A Wish for Destruction: The Life and Death of the Herzliya Gymnasium Building. Gymnasium days: the Herzliya Hebrew gymnasium, 1905–1959. Ed. by G. Raz. Tel Aviv, 2013. P. 26–47. In Hebrew.

Alon-Mozes 2011 – Alon-Mozes T. Rural ethos and urban development: the emergence of the first Hebrew town in modern Palestine. Planning Perspectives. 2011. Vol. 26. 2. P. 283–300.

Azaryahu 2006 – Azaryahu M. Tel-Aviv Mythography of a City. New York. 2006.

Ben Artzi 2006 – Ben Artzi Y. Alexander Baerwald’s Study Tour in Palestine. Zmanim: A Historical Quarterly. 2006. 96. P. 14–21. URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23443655?refreqid=excelsior%3Ae47ee9a1e1c3ae4f107dcd3837d6aae6. In Hebrew.

Buber 1967 – Buber M. On Judaism: An Introduction to the Essence of Judaism by One of the Most Important Religious Thinkers of the Twentieth Century. Ed. by Nahum N. Glatzer. New York, 1967.

Goldstein 2020 – Goldstein D. Tel Aviv, habibi, Tel Aviv. Makom beolam. Haifa, 2020. URL: https://herzl.haifa.ac.il/images/Item_31267259_20200805085713.pdf. In Hebrew.

Kahanov 1974 – Kahanov F. Yishuv culture in Jaffa and the creation of the Neve Tzedek quarter. Memories of the Eretz Israel. Ed. by A. Yaari. Vol. 1. Ramat-Gan, 1974. P. 623–625. In Hebrew.

Kalmar 2001 – Kalmar I. Moorish Style: Orientalism, the Jews, and Synagogue Architecture. Jewish Social Studies. History, Culture, and Society. 2001. 7 (3). P. 68–100.

Katz 1985 – Katz I. Ahuzat Beit Company 1906–1909 – laying the foundations for the establishment of Tel Aviv. Cathedra. 1985. 35. P. 161–191. In Hebrew.

Kravtsov 2008 – Kravtsov S. R. Reconstruction of the Temple by Charles Chipiez and Its Applications in Architecture. Ars Judaica. 2008. Vol. 4. P. 36–37.

About author

Vladimir G. Ruzhansky

Lecturer of Departмент of World History and Foreign Regional Studies

Russian-Armenian University, Yerevan, Armenia

E-mail: [email protected]

For citation:

Ruzhansky V. Zionist Architecture of the First Two Decades of the 20th Century: from Orientalism to Occidentalism. Urbis et Orbis. Microhistory and Semiotics of the City. 2021. 1. P. 172–188. DOI: https://doi.org/10.34680/urbis-2021-1-172-188