DOI: https://doi.org/10.34680/urbis-2025-5(1)-96-10

Festive processions and city ceremonies in Tudor London

Svetlana Mednis

The State Hermitage Museum, St. Petersburg, Russia

ORCID: 0000-0002-7575-9607

ABSTRACT

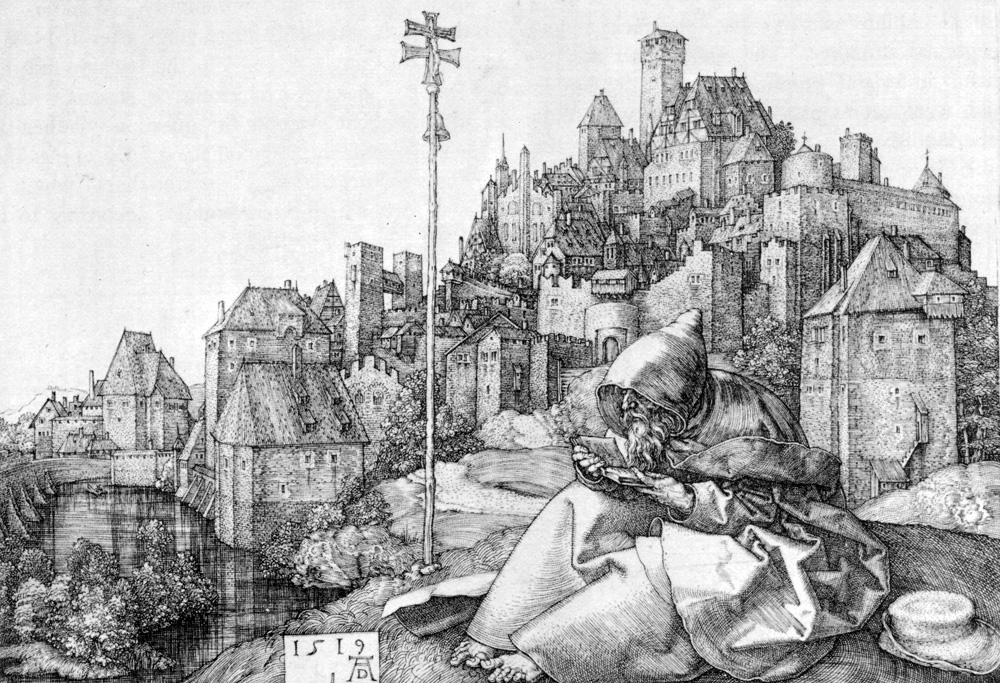

The European cities were among the most critical institutions, characterized by complex social, economic, political, and cultural systems of relationships. They evaluated the increase in medieval corporations and interaction with the English court. Additionally, European cities served as the stage for a ritualized form of publicity. Royal entrances, initiation ceremonies, processions, and carnivals emphasized power relations. The performances reflected the legitimization of the royal power and its prestige. They demonstrated the status of corporations in the social system. The scripts included mythical and biblical allegories and consisted of a specific order of actions and staging logic. The scenic elements are based on space, social hierarchy, and philosophy. This article examines urban processions and festivities in sixteenth-century London based on city chronicles and civic calendars from the Tudor period. A cultural-anthropological approach is applied to explore the structure and symbolism of royal wedding processions, the inauguration ceremonies of the Lord Mayor, and theatrical masques within the urban space. Although these public celebrations trace their roots to medieval traditions, under the Tudors, they acquired features of triumphal spectacles. Special attention is given to the wedding entry of Catherine of Aragon in 1501, interpreted through the lens of Arnold van Gennep’s concept of rites of passage. This approach highlights the transformation of the bride's social status and her integration into the English royal court. The Lord Mayor’s inauguration is analyzed through its social, economic, and legal dimensions, revealing the vassal–seigneurial relationship between the City of London and the Crown. The evolution of royal masques is discussed in the developments at the Tudor court. These public rituals not only showcase the rich culture of Tudor London but also reflect the social hierarchy and worldview of both its citizens and the nobility.

KEYWORDS: London, Tudors, royal processions, masks, medieval city, cultural anthropology.

References

Anglo, S. (1963). Spectacle, pageantry, and early Tudor policy. Clarendon Press.

Bergeron, D. M. (1970). The Elizabethan Lord Mayor’s Show. Studies in English Literature,1500–1900, 10(2), 269–285. https://doi.org/10.2307/449917

Chernova, L. N. (2022). Publicity as a factor of the formation of city government in England in the 14th–15th centuries (based on London). ISTORIYA, 13(1). https://doi.org/10.18254/s207987840018810-0 (In Russian).

Elias, N. (2002). The civilizing process. Blackwell Publishing.

Fyodorov, S. (2023). Knighthood and titled nobility in the antiquarian episteme of the 16th–17th Centuries. ISTORIYA, 14(7). https://doi.org/10.18254/s207987840027294-2. (In Russian).

Hill, T. (2017). Pageantry and power. A cultural history of the early modern Lord Mayor’s Show 1585–1639. Manchester University Press.

Khachaturyan N. (2020). The royal court in the institutional history of Western European medieval statehood (on the issue of continuity in the development process). ISTORIYA, 11(10). https://doi.org/10.18254/S207987840011669-4

Khomenkova, V. Yu. (2023). Sir John Fern and formation of antiquarian narrative on nobilitas. Srednie Veka, 84(3), 198–215. https://doi.org/10.7868/S0131878023030108. (In Russian).

Kipling, G. (1990a). Enter the King: theatre, liturgy, and ritual in the medieval civic triumph. Clarendon Press.

Kipling, G. (1990b). The receyt of the Lady Kateryne. Oxford University Press.

Kovalev, V. A. (2012). From theatre to ritual: symbolic images of the royal power in the court theatre of King James I Stuart, triadic model and making of the dynastic mythology. Studies in Medieval and Early Modern Social History and Culture, 9, 162–178. (In Russian).

Lancashire, A. (2002). London civic theatre: city drama and pageantry from Roman Times to 1558. Cambridge University Press.

Mosolkina, T. V. (2017). A social history of England of the XIV–XVII centuries. Center for Humanitarian Initiatives. (In Russian).

Nichols, J. (1831). London pageants. J. B. Nichols and Son.

Palamarchuk, A. A. (2024). Heraldic tracts in the Tudor and Stuart England. Vestnik of Saint Petersburg University. History, 69(1), 89–99. https://doi.org/10.21638/spbu02.2024.106 (In Russian).

Smith, T. (1870). English guilds: the original ordinances of more than one hundred early English guilds. N. TRÜBNER & CO.

Svanidze, A. A. (Ed.). (1999–2000). The city in the medieval civilization of Western Europe: in 4 vols. Nauka. (In Russian).

Traill, H. (1897). Social England, vol. 1–3. Cassel and Company.

Twycross, M., & Carpenter, S. (2016). Masks and Masking in Medieval and Early Tudor England. Routledge.

van Gennep, A. (1999). The rites of passage. University of Chicago Press.

Weir, A. (2018). A Tudor Christmas. Jonathan Cape.

Withington, R. (1918). English pageantry: a historical outline. Harvard University Press.

Information about the author

Svetlana S. Mednis

Research Fellow of the Numismatics Department

The State Hermitage Museum

34, Palace Embankment,

St. Petersburg, 190000, Russian Federation

ORCID: 0000-0002-7575-9607

e-mail: [email protected]

For citation:

Mednis, S. S. (2025). Festive processions and city ceremonies in Tudor London. Urbis et Orbis. Microhistory and Semiotics of the City, 5(1), 96–104. https://doi.org/10.34680/urbis-2025-5(1)-96-10